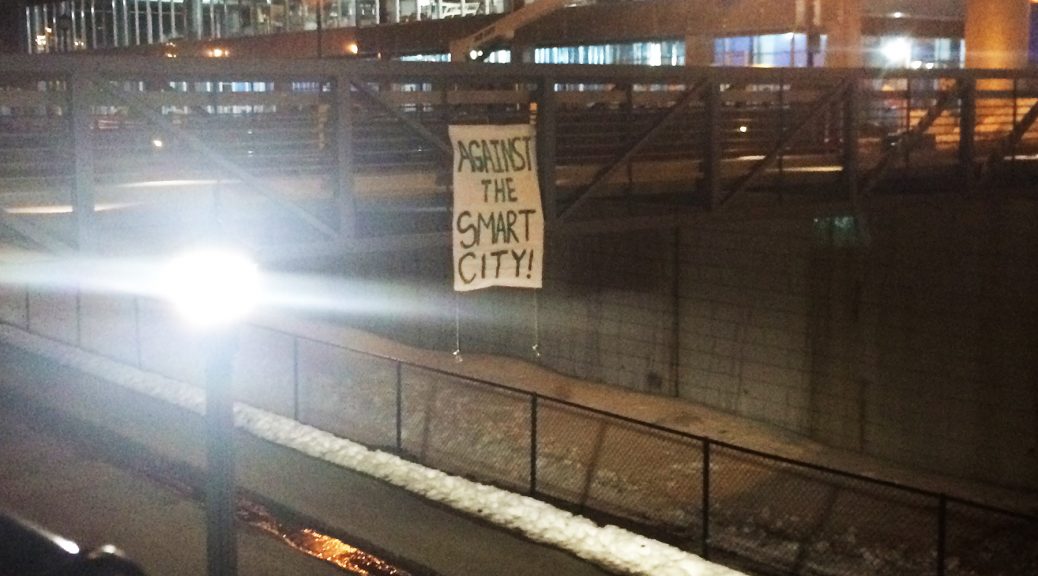

In April Hennepin County ran the latest demonstration of the EasyMile EZ10, which is not an overpriced treadmill as the name suggests but rather a self-driving shuttle, on the greenway in Uptown. This followed a run of demonstrations along Nicollet Mall that took place during the lead-up to the Super Bowl earlier this year. However, before the test run/photo op could begin a banner was affixed to a bridge directly over the test site reading “Against The Smart City!”

This action resonates strongly with us, so we’re using it as a starting point to elaborate this rallying cry, against the smart city. In the words of the anonymous communique, originally submitted to Conflict MN:

“While touted as progress, there are still those of us who see these projects as only the further deepening of the desert. As our cities become increasingly automated, this process attempts to eclipse not only the possibilities of revolt, but even that of a life of anything but its perpetual (re)production. These automated shuttles will be yet another vehicle for funneling citizens between where they work, shop, and sleep, as mindlessly as the shuttle which carries them.”

The ones who dropped the banner identify these automated shuttles as a new piece in a mosaic of projects designed to smooth the flow of people and capital within the metropolis. In other words, the city is designed to make sure that the only possible forms that life can take are that of producing or reproducing the capitalist, white supremacist, patriarchal reality. Although there are not yet plans to permanently deploy the shuttles locally, these tests give us a glimpse of the future form cities will take if no one intervenes.

Most often, these projects are criticized for their role as harbingers of gentrification. And there is no doubt that these shuttles were never meant for the poor. However, we feel the need to expand our critiques. We aren’t opposed to these projects only because they cause displacement, but because they create a way of life we refuse to live.

The smart city is not only the way in which bodies are transported throughout the metropolis. As the name implies, the premise of the smart city can be boiled down to the logic of the smart phone applied at the municipal level. In their 2014 book To Our Friends, the Invisible Committee sketch out a broader picture:

“Behind the futuristic promise of a world of fully linked people and objects, when cars, fridges, watches, vacuums, and dildos are directly connected to each other and to the Internet, there is what is already here: the fact that the most polyvalent of sensors is already in operation: myself. “I” share my geolocation, my mood, my opinions, my account of what I saw today that was awesome or awesomely banal. I ran, so I immediately shared my route, my time, my performance numbers and their self-evaluation. I always post photos of my vacations, my evenings, my riots, my colleagues, of what I’m going to eat and who I’m going to fuck. I appear not to do much and yet I produce a steady stream of data. Whether I work or not, my everyday life, as a stock of information, can always be mined. I am constantly improving the algorithm.”

The automated shuttle was, of course, not the only thing tested during the Super Bowl. Local law enforcement began using FieldWatch, an app that allows police officers to stream video directly from their phones to the command center, at the time staffed by nearly one hundred people. Along with newly installed surveillance cameras, this gave law enforcement a real time view of virtually the entire downtown terrain. While the Super Bowl festivities have left, the police continue to take advantage of their new tools, and have even requested the installation of another thousand cameras.

Looking at these shuttles and cameras alongside the proliferation of new light fixtures such as on Lake Street underneath Hiawatha (as we wrote about in Issue 9), we start to see what the pieces in the mosaic form. Not only a city devoted to the total surveillance of public space, but also the shaping of that space to eliminate the possibility of any disturbances. In other words, “a terrain where all that can happen is what has already been predicted and planned” to quote from this latest communique. Or, as the Invisible Committee wrote:

“The stated ambition of cybernetics is to manage the unforeseeable, and to govern the ungovernable instead of trying to destroy it. The question of cybernetic government is not only, as in the era of political economy, to anticipate in order to plan the action to take, but also to act directly upon the virtual, to structure the possibilities. […] In this vision, the metropolis doesn’t become smart through the decision-making and action of a central government, but appears, as a ‘spontaneous order,’ when its inhabitants ‘find new ways of producing, connecting, and giving meaning to their own data.’”

This “spontaneous order” occurs because the potential for disorder has been foreclosed on by the very structure of the city. Not only do these surveillance projects allow the police to track those they designate potential criminals, they psychologically impact our behaviors and encounters—this is the real panopticon effect. While disorder can never be completely eliminated, the smart city is designed for its maximum attenuation. And to put our cards on the table, we greatly prefer disorder over the world as it exists.

How could we not? It’s clear to everyone that there is something deeply wrong with the state of affairs today. We are told that there are proper, legal channels through which reform will happen—but these channels are only yet another way to structure our possibilities.

The Against The Smart City communique offers a few words of encouragement, with which we’ll close:

“While their fantasy is to build a terrain where all that can happen is what has already been predicted and planned, we know that fundamentally life cannot be reduced to data and in its flux escapes prediction and control. Don’t wait for others to take action for you. Take it yourselves.”