Recently we were pleased to notice that a number of issues of various radical publications from Minnesota’s past had been uploaded to counter-information site Conflict MN. Digging into the history of struggles that have taken place in this land has always been an important part of Nightfall, so we want to amplify some of the perspectives contained within the pages of these publications with a new semi-regular feature. Each column will spotlight a different publication, giving an overview of some of the topics covered in its pages as well as reprinting excerpts that seem particularly relevant to our contemporary struggles. This feature will start with our next issue, but first we want to lay out some thoughts on the place of radical publishing in a larger liberatory movement. In the meantime we encourage you to head over to Conflict MN to read the publications for yourself.

Why write? It’s a question that keeps popping up in my head lately. Some who do this work hold that we can free ourselves from the domination of the capitalist world by taking up the tools of image production and using them for our own purposes, rendering the dominant media obsolete by becoming the media ourselves. For me, however, the goal of becoming the media has always rung hollow. I don’t want to be the media, I want to be free, and a world where we are all constantly producing and sharing content with each other strikes me as something less than a utopia. Indeed it would not be far-fetched to argue that social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter have in fact fulfilled the promise of a world in which the people who consume content are at the same time those who produce it, yet the isolation and pacification associated with older forms of mass media remain, and in some ways have even deepened.

The problem is not just that Facebook is a hierarchical corporation raking in ad-revenue off the interactions of its users, or that most Facebook posts are actually other people’s words that we repost as stand-ins for original expressions of our own thoughts and feelings. The problem is that no matter how horizontal a form of media becomes, if it solely leads to its own reproduction rather than the production of new and more vital ways of organizing our lives and deepening our bonds with each other in the real world then it is ultimately just another strand in the web of spectacle that keeps us from confronting the emptiness of our lived experience. This is often just as true for self-consciously radical media as it is for mainstream entertainment, as making and consuming more and more woke critiques of the existent from the comfort of one’s home can often end up acting as a stand-in for putting any effort into any real world projects or relationships.

Nonetheless, I know that writing can also act as a spark to set off the powder keg of the daily resentments and frustrations we all face in our daily lives, opening us up to something more. While I definitely at times can slip into a cycle of endless mediated passivity, my own life and practice have been enriched again and again by being exposed to the experiences of people with different perspectives than my own. Clearly those who want everything to stay as it is recognize the destabilizing potential of certain types of media practices too, leading to regulations such as one recently instituted at a number of New York prisons limiting written materials to a list of 50 pre-approved texts consisting almost entirely of romance novels, religious works and coloring books. Apparently prison administrators suspected that books prisoners were reading were giving them too much perspective on their position within the modern prison-slave industry, leading to them being increasingly harder to control.

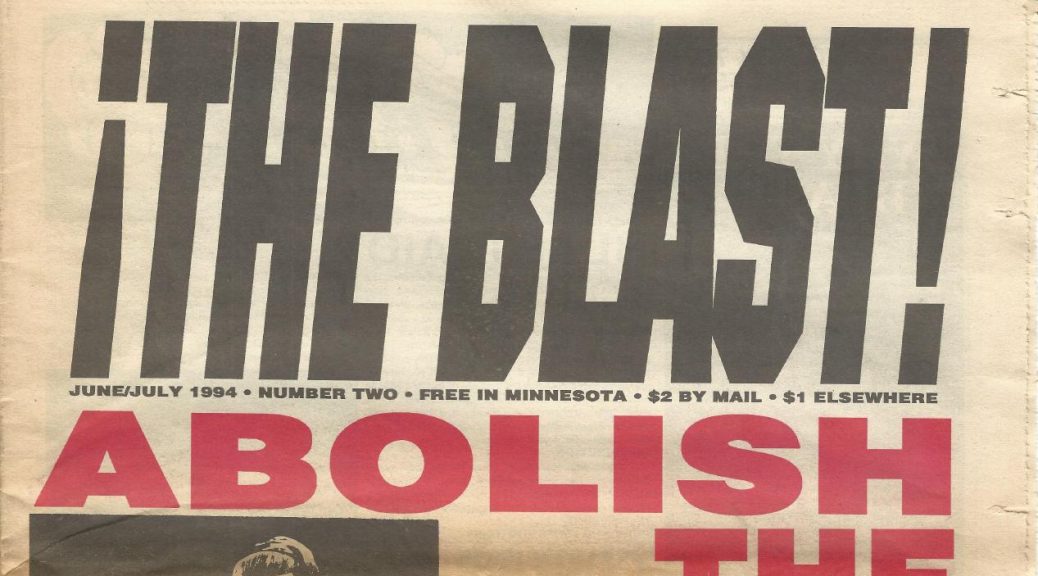

What then separates media that connects us and enriches our lives from media that isolates and pacifies, if it is not just a matter of being far enough to the correct side of some spectrum of radicalness? I don’t have any concrete answers, but I suspect that often the answer is not actually innately embedded in whichever fragment of media that is under consideration but rather in how it is put to use by those who interact with it. This idea certainly seems to be supported when I look over issues of the publications we intend to spotlight more in this space in the future, such as Daybreak, an anarchist newspaper from the early-2000’s rooted in DIY culture; Anpao Duta, a Dakota journal of decolonization from the late 2000’s/early 2010’s; and The Blast, an anarchist newspaper from the 90’s with a wide range of coverage but with especially strong coverage of prison resistance.

A persistent feature of all of these publications is articles focusing on introducing key radical concepts, such as autonomy and decolonization, providing points of entry into the themes being explored in these papers for people who may be less versed in radical ideas so as to introduce them to anti-authoritarian politics. For people who have already been exposed to those ideas, however, what is most exciting and energizing to read through are the articles that combine reports of local happenings that were often ignored or diminished by mainstream outlets at the time with analysis of how these efforts can function together to build up vibrant networks of resistance. For example, reports on confrontational actions such as the clashes between police and North Minneapolis residents that took place in 2002, covered in Daybreak #3, or the arson of a museum in southeastern North Dakota celebrating the Whitestone Hill Massacre of 1863, covered in Anpao Duta #4, share pages in these publications with articles on community efforts to establish autonomy from corporate medicine and the agribusiness industry.

In addition to rescuing these happenings from the waste-bin of history, these articles give the impression of being both firmly rooted in and feeding back into the struggles and movements taking place at the time. There seems to be a clear recognition on the part of many of the articles in these publications that the point of writing and reading should always be to thoughtfully and deliberately consider the problems we face in a way that will serve to enrich our actual lived experiences, rather than simply build up an intellectual identity or brand to show off to others. In this respect I think it is no coincidence that these publications were all wholly or primarily print-based. The effort involved in writing, designing, printing and distributing an actual physical publication forces you to be very deliberate about what you want to communicate and what you intend to get out of it, something that is rarely true for writings distributed online.

“I detest writing” opens Russell Means in his essay “For America to Live Europe Must Die,” which is appropriately not actually an essay but a transcription of a speech. “[Writing] is one of the white world’s ways of destroying the cultures of non-European peoples, the imposing of an abstraction over the spoken relationship of a people.” Means consents to have his words written down only so as to reach into the pockets of the world where the written word is considered the most valuable and authentic form of communication, that is the Western world, and see if he can touch the hearts or minds of any people who find themselves positioned there. This goal, to use writing against the systems of control which birthed it, is as close as I can come to a mission statement for a project like this. If it leads us, both as writers and as readers, to starting conversations, asking questions, and listening more to the people and the world around us then it is a good thing. On the other hand, if it only leads to more reading, watching, and writing, continually chasing that next edgier burst of information, well then that will be the time for us to lay down the pen and paper and step outside.